I.

When we say a city is old we must always think of the scale in which we speak. Americans might say that Boston is an old city, for it was founded in 1630, almost 400 years ago. The English would say that London is an old city, for it goes back to the days of Rome – who is old indeed. The Greeks would say Athens is an old city, for she was fighting against Darius the Great while Rome was but a muddy village struggling for life in the unimportant west. The people of the ancient middle east would scoff, for they know that there were cities that existed there before Greek was even a language. Babylon, ancient of cities, was founded 2500 years before Christ, and even she was not the oldest. But all the cities that old are gone now, having been destroyed and abandoned long since. Some few have been rebuilt in the centuries after their destruction, and some were so old that even after centuries in ruin the cities built on their ashes are now ancient themselves.

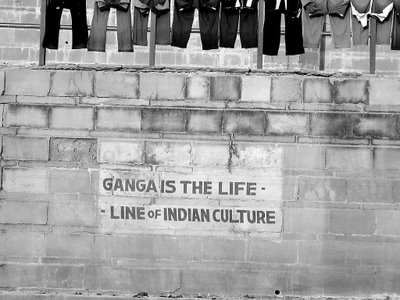

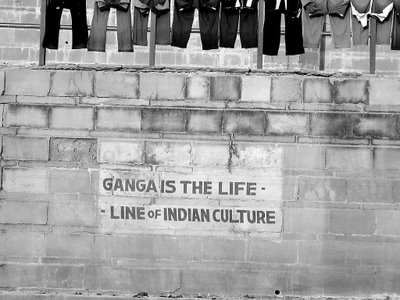

But when you say that a city is old in India you must compare it to Varanasi. Varanasi is older than Latin or Greek as languages, older than Christianity and Islam put together, possibly older than Babylon, and maybe nearly as old as Sumner itself. 5000 years ago, at nearly the same time as the pyramids of Egypt were having their foundations laid, the first pilgrims came to Varanasi to wash their bodies, burn their dead, and send their prayers to the gods. And in the 5000 years that have followed, 5000 years in which every major religion of the earth has had its holy books written, they have never stopped coming. In Varanasi this day you can see the remains of rites that are as old as the mythic cities of the Tigris and Euphrates, as old as the pharaohs, and yet are still practiced where all their contemporaries have passed two millennia into the dust.

To be in Varanasi is to be overwhelmed with the knowledge of humanity's vastness. Seeing the women clothed in bright silks bathing, the corpses being placed on sandalwood pyres to burn, and the ashes and dirt of both being washed away down the sacred river Ganges is to know how small you are in the face of the world. Before the father of the father of the language I write in was first spoken people came to this spot and worshiped and lived and died.

Earlier this year I was in Chicago and I looked up at the Sears Tower from the base and saw what humanity has built, how far we have come. A few days ago at Varanasi I looked from the base of the ghats back through history and saw how far we go. The two together are dizzying, but I tell you straight that the view in Varanasi caused me even more vertigo, for it is a longer distance back than any building could ever hope to be up.

II.

Unlike Chicago or Rome, the story of Varanasi is not to be found in her buildings. Invader after invader has swept through Varanasi's five millennia of life and they have all brought fire with them. There is actually little physical in this most ancient city that is ancient at all. Most of the ghats and the buildings around them are less than 400 years old.

Once you come away from the ghats and the sacred river most of Varanasi does not even look old. It certainly looks decrepit, but it seems more a shell burned out too fast by hard living rather than a venerable old man come to a ripe age. And in many places the hard painted streaks of globalization and modernization stand out. Billboards for movies, gold and silk shops, Xbox 360s, and every other consumer good are thick in many of the streets. Petrol stations and high rise hotels crowd the temples shoulder to shoulder, pressing each other for space enough to breath in the narrow roads that are always choked with smog from the millions of autos that pass through the city in endless clamoring, honking waves.

In this most ancient of cities the story of age is found in the people and in their rites. Varanasi is the history of humanity written in flesh and ritual. To come here and learn one cannot look at the safe and controlled walls of ancient structures, now relegated to exotic names of dead dynasties. One must look at the people on the ghats, the thronging, screaming, filthy masses filling the streets and see what history has written upon them, what history they write with their very lives.

III.

Varanasi is sacred to Shiva, and it is a city of temples. If you go into any tall building in Varanasi you will be able to look down a see a temple, and probably five or six, all within the range of a baseball pitch. Most of all the ghats are choked with temples, so full that temples were built too far down into the river and are now being claimed by the sacred river Ganges. They too will pass, as all the humanity that has come here has passed, and such is fitting in a city sacred to the Destroyer.

The Ganges, sacred river of thousands of years, so sacred that its geography was mimicked in Java and Cambodia to give credibility to the reigns of kings who would never have a single member of their dynasty come within 1000 miles of the waters, is at its most sacred as it passes the ghats of Varanasi. To die and be burned here, to have your ashes given to the waters, is to attain Moksha – salvation. The trains to Varanasi are thus choked with the dying, old men and young girls sagging in the supporting hands of their families, trying to hold on long enough to see the sacred river, to die knowing that they have come to the banks of eternity and may now pass on to the other side.

At dawn and at evening it is hard to walk along the ghats, for they are so crowded with humanity that passage is a trail of shoving, jostling, milling crowds that move with the same slow tide as the sacred river itself. Naked sadhus and pious Brahmins, widows with begging bowls and priests chanting mantras press against you and block the way. Humanity is everywhere, in every color and shape and state of life, under the towering gopams of the Small Pox temple.

Gods and temples, the living and the dying, the bathing and the burning: in their churning, milling, screaming masses Varanasi is sacred.

IV.

In the midst of all this age and sacredness, in the confluence of all this karma and devotion, it should come as no surprise that Varanasi is a pit. It is a dirty, nasty, reeking city full of people who are angrier, less hospitable, more violent, ignorant, ugly and selfish than anywhere else I have ever been. The sheer ugliness of the hatred and selfishness I saw on face after face in Varanasi would be shocking in the worst neighborhoods in Los Angeles, and in India it was nearly enough to take my breath. In a country in which I had never passed through a city in which a dozen people did not invite me to their homes for a meal I found myself alone in Varanasi.

So busy is the city, and so accustomed to death and the passing feet of people who only come here to pray and leave or die and leave, that in Varanasi it is rare for one individual to care about the passing of another. Only the touts reach out their hands to you, for in this city those whose intentions are elevated are too busy to pay attention to you for they must attend to their own karma.

Throughout India I rarely saw violence, though I sometimes heard of its passing close before or behind me. But in Varanasi I saw it paraded through the street like the idol of a god. Dozens of rickshaw drivers beat each other bloody on the streets every day I was there, and their brawls threatened to turn into riots until police with machine guns came and beat them into submission. Mo and I were assaulted one night when our rickshaw got stuck. Men on the street screamed at us and demanded money, and when we did not give it to them they hurled trash and bricks at us while our driver struggled to get us clear. We were not hurt, but it was more because the men were drunk than because of any beneficence in the city.

In the ancient city of Varanasi, holy to gods and men alike, there is ugliness and brutality on display just as open and just as ancient as the sacred prayers and holy fires. It is a city where degradation, hate, and filth daily rinse against the ghats, a putrid river of rancid karma that seems at war with the sacred waters of the Ganges. Here life comes out from behind its masks and lets you see it true: profane and sacred all at once, brutal and brilliant and always, always defying your expectations.

V.

On our last night in Varanasi Mo and I went out on a boat to do puja on the Ganges. While the conch shells wailed in the background, accompanied by the brass clash of temple gongs and the ululating calls of the Brahmins' mantras, our guide helped us and our group light hundreds of little candles that were placed in leaves filled with flowers. They told us to give the candles to the waters, along with a prayer to whatever god we might worship. For each candle we were to give a different prayer: for ourselves, for our family, for our country, for our world.

Our group put hundreds of the candles into the water. Some of them tipped and vanished under the surface almost instantly, or were lost under the hull of the boat as it glided through the night. Others streamed out behind us, staying lit for hours as they drifted away down that dark stretch of river that has taken so many prayers, so many lives, over the millennia. When all the candles were in the water we sat quietly, watching them drift away as the sounds of the city filtered gently around us. It was a moment of silence, of peace, and for me of something aching and sweet and terrible.

I wrote this poem as we sat in the boat, looking out at the candles in the night. It came to me suddenly, and I spoke it aloud to Mo. With her help I remembered it later and wrote it down. It is my last statement about Varanasi, and the Ganges, and that night.

This thin line of lights

This thin line of lights

Is a history of prayer;

Candles in leaves and flowers

Upon the sacred water.

In this darkness I cannot tell

Which is yours and which mine

Nor which still burns bright

And which has sputtered and died.

All I know is that tonight all prayers

Are our prayers together, and that

All will be lost to the water,

To the darkness, and to time. -Robins 10/12/2006