Later Skaters!

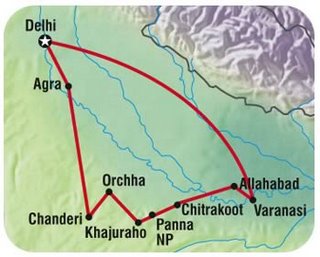

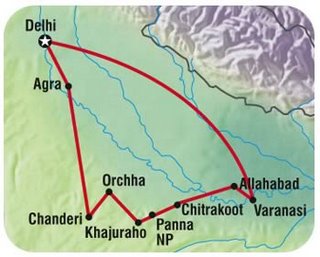

Oh yeah, and add Bangalore and Jaipur to the routemap above.

Unless we snag an internet cafe along the way, talk to you in three weeks when I get back to work!

FIVE years have passed since the assault on New York City by the ruthless emissaries of Osama Bin Laden on September 11, 2001. Before they were brought crashing down that fateful day, I could see the twin towers of the World Trade Center from the building in New Jersey in which my office was located.

As it happened, I was in New York that day, working at home, and so I did not stand at the windows of the building, as many of my colleagues did, staring at the macabre view of smoke billowing out from the buildings and over the skyline of the city itself, the very quintessence of everything modern for millions of people across the globe.

In the days immediately after 9/11, everything felt different in the urbane city. The 1990s were great years for New York — or rather, more accurately, the richest and flashiest of New Yorkers, those who flowed seemingly endlessly into Manhattan, driving rents and real estate prices up, up and up, so that the working poor and even the middle class were increasingly squeezed out of neighbourhoods, including those that they had in fact reclaimed to live in and, by their living, made liveable. In the immediate aftermath of the attacks, the divided city seemed to forget its divisions. Clichés began to ring true — all the city's residents were helpful neighbours, all its men were tall, all its women caring.

Tragic touch

And who could dare deny that it was so, that all this was indeed true? It is in the nature of events like 9/11 to make truths out of clichés. They sanctify with their tragic touch. No one who died in the attacks deserved to die, not in this way. Terrorism is indiscriminate in its violence; or, if you prefer, much too righteous in its notion of guilt and innocence. And because terrorism is so, it makes towering saints of its victims. People like to say there are two sides to every story. But when it comes to an event like 9/11, many behave as if there is only one — the side of the saints of 9/11.

The consequences of such onesidedness are great. To thousands of people in far-flung corners of the globe — in Afghanistan and Iraq and in other places — they are as great as the consequences were to the saints of 9/11. Thousands in these places (by now in far greater numbers than died in New York and elsewhere on 9/11) have already paid for that fateful day with their lives as the armies of Britain and the U.S. rain missiles and bombs from the sky.

A superpower goaded to vengeance is indiscriminate in its pursuit of the terror of war; or, if you prefer, much too righteous in its notion of guilt and innocence. Thus, more sanctity enters the world, only now on the other side.

The saints of 9/11 stand ranged against the saints of the torture cells of Abu Ghraib and the murdered innocents of Haditha and countless other villages and towns across the "New Middle East". These other saints too did not deserve to die, not in this way. They too are all without blemish now.

Who could ever do the grisly arithmetic here? What matchless accountant could ever balance this ledger book of tragedy to even a single person's satisfaction?

Five years after. New York is the same beguiling city that it ever was, imperial and self-indulgent and narcissistic and liberal and tolerant and welcoming, all at the same time. Immigrants flow into the new America as they did into the old, even as many Americans grow more and more vocal in their opposition to their arrival. Osama is still free, and the war on terror shows no sign of ending, even as the American public grows tired of their country's continued entanglement in ceaseless conflict.

Memorial

What has been achieved in the five years? In the arithmetic of saints the answer will always come out to zero. What we need is not arithmetic, but something else altogether. A memorial is in the planning for where the towers of the World Trade Center stood, but the towers themselves will never again rise over New York.

The hole at the heart of this great American city, for better or for worse the most potent symbol we have for modern civilisation, cannot be measured by the arithmetic of revenge. Nor can the hole at the heart of the "New Middle East" that we are being told is being born in Iraq and Lebanon and elsewhere in West Asia by the British and the American leaders.

Anniversaries and arithmetic are for remembering, which is important and necessary in its time and its place. But forgetting too has its time and place.

If Americans, and indeed all the good people in India and in the world at large, memorialise 9/11 today, can we tomorrow fail to memorialise the hundred tragedies — many the result of deliberate American policy in the pursuit of oil and other economic and political interests in West Asia — that led to 9/11?

If all we do is remember, when is there time to stop more tragedies, more occasions for bitter memorialising, from entering the world?

Multiply 9/11 by 5? Maybe you shouldn't.

SEPTEMBER 11 is a date forever etched in our minds. The terrorist attacks on the United States in 2001 inaugurated a new era of uncertainty, fear, and hatred. For some influential sections in the West, these attacks have reaffirmed a belief in an inevitable "clash of civilisations'. Such a binary view of the world coupled with an opportunism has led to the invasion and occupation of Iraq, and more recently Israel's brazen assault on Lebanon. After decades of unprecedented peace, the mindless bombings in Madrid and London have introduced a new and gruesome dimension to European life. Given the political and economic preponderance of the West, the impact of these events is felt worldwide. Thus, at home, the terrible bombings of Mumbai's trains are now viewed as a part of this global menace.

Despite the disbelief of its citizens and feigned innocence of its leaders, America's international record has been far from simon-pure. It is in response to such duplicity that alert minds have reminded us of another 9/11. On the same date, in 1973, the democratically elected President of Chile, Salvador Allende, was overthrown in a coup that was aided and abetted by the American Government. With Allende dead, Chile rapidly descended into a long era of darkness under the right-wing Augusto Pinochet.

Other lessons

But the messy history of humankind also holds other lessons for those alive to its metaphors. In 1892, America commemorated the 400th anniversary of Columbus' "discovery" by organising a year-long Exposition in Chicago. On the margins of this event, a meeting of religious figures was organised. Addressing this gathering, on September 11, 1893, Swami Vivekananda famously drew attention to the consequences of "sectarianism, bigotry, and its horrible descendant, fanaticism". While Vivekananda upheld tolerance as the key to humanity's future, yet another 9/11 coincidence provides an even more edifying story of human dignity and freedom.

In September 1906, the Transvaal legislature in colonial South Africa sought to curb the growing economic influence of the Indian community through a racially motivated "Asiatic Ordinance" that, amongst other measures, included mandatory fingerprinting. On September 11, 1906, the Indian community in Johannesburg gathered at the Empire Theatre, a Jewish institution, and vowed to resist the proposed legislation. Amidst vigorous discussions, Haji Habib, an elderly Muslim, arose and made a solemn pledge of peaceful civil disobedience, with "God as witness". That the Indian opposition to the proposed legislation would be entirely non-violent was never in question. However, Haji Habib's solemn oath in the name of God was a moment of epiphany for a man who would change the course of history. That man was Mohandas Gandhi, the Mahatma.

An idea takes shape

Although known for leading the Freedom Movement in India, Gandhi's philosophy and its practice were painstakingly crafted over a period of two decades in South Africa. The 9/11 meeting helped crystallise a nascent idea in his mind. Gandhi's own form of non-violent, direct action, Satyagraha, was born. An immensely significant idea, Satyagraha is notoriously difficult to translate into English. Etymologically, satya means Truth and agraha means insistence, implying a steadfast insistence of the Truth. Acting on the dictates of individual conscience in the cause of justice is an old idea present in various forms in all societies. However, it was Gandhi who elevated a personal, ethical tenet to a philosophy of large-scale social and political action that transcends time and geography.

Satyagraha has been much used, and abused, in the hundred years since Gandhi first formulated its basic tenets. While thousands took part in India's struggle against British rule, many years later in distant America, Satyagraha found expression in the life of Martin Luther King Jr. and the Civil Rights Movement. In independent India itself, while Gandhi has been increasingly forgotten, Satyagraha has been frequently reinvented by a variety of movements for social and ecological justice.

Satyagraha has unfortunately been confused with Pacifism which has its roots in Western history. Ironically, such a conflation erases the very reason for the invention of the word. Gandhi, with help from his nephew Maganlal, coined the neologism as he felt the term used to describe his ideas, "passive resistance", was wholly inadequate. In particular, Gandhi felt that the description of his method as a "weapon of the weak" was objectionable. Satyagraha is anything but passive or weak. It is no idle piety, or woolly-headed craving for peace with no reference to the complexities of the real world. Rather it is a militant, but resolutely non-violent assertion of one's moral beliefs. Gandhi held that humans were inherently capable of both good and evil. Therefore, faced with injustice, it was one's responsibility to rouse the moral sense of an opponent. While many thinkers acknowledge the inevitability of war and strife in society, Gandhi stubbornly refused to accept violent retribution as an answer to an evil act. "An eye for an eye makes the world blind," he famously declaimed. While a violent response would make us lose our intrinsic humanity, he did not imply silent acquiescence to injustice. In fact, he held that violence was preferable to meek acceptance of oppression. However, a better world was only possible by demanding and obtaining justice through peaceful means.

Stroke of genius

The Application of this philosophy on a national scale was a stroke of rare genius and a courageous, often bordering on foolhardy, act of self-belief. It was hard enough for any individual to maintain a non-violent stand in the face of severe incitement and violence. To demand that of an entire mass struggle was unthinkable for many. But the virtue of a large-scale peaceful struggle in India triumphed and heralded the waves of decolonisation that swept across Asia and Africa. Colonial empires ultimately crumbled under the weight of the manifest truth that Freedom was everyone's birthright.

Unlike most forms of political organisation and action, Satyagraha yields no corner to realpolitik and our many daily compromises. This is so, as one's loyalty is completely given over to the only principle worth upholding — Truth. For Gandhi, this was the highest form of religion. "Truth is God", he often said. Thus the creed of Satyagraha also demanded that its practitioners freely accept their errors. Frequently, and always publicly, Gandhi would himself proclaim his errors, his `Himalayan blunders". In the process, he infused a new sense of vitality and purpose into our public life that has, sadly, receded.

Gandhi provided humanity with a non-violent, moral weapon. In a world riven by unending violence, oppression and conflict its relevance is self-evident. Beyond the symbolism of this "other 9/11", Gandhi's insight that came to the fore a century ago holds the possibility of building a world based on genuine peace and justice, where genuinely "enduring freedom" can prevail.