Murali

In Mamallapuram there were many of the patriotic Indians, gathered in the World Heritage site to celebrate their nation's independence who would stop to shake our hands and talk to us for a few minutes. One of the things they loved so much about coming to places like this was the chance to meet folks from far away. In the midst of the farmers from Andhra Pradesh who had never seen a white person before and the jaded cosmopolitans of Mumbai who had seen all too many there was a man who had been born in a small town, grown up in a big city, and spent a year and a half in Chicago working as an engineer for Ashok Leland – one of the largest auto manufacturers in India.

While Mo and I were in the Shore Temple, looking into the shrine of Shiva in the far back of that monolithic structure, this fellow offered me his hand and asked me if I knew the history of the place where I was standing. Behind him his wife was laughing at him, saying "Oh Murali!" and his brother was shaking his head with the kind of dismay that said very clearly that Murali was at it again – talking to the Americans.

I shook his hand and grinned and said, "I know a little, it was…" and proceeded to tell him the story that I told in my entry Mamallapuram I. This both delighted, startled, and slightly concerned him. He was, all at once, happy that I knew about his country, surprised that I knew so much, and a little concerned that I might know more than him. But as I settled in to pump him for further information he relaxed, though his wife and brother continued to laugh at him and his odd ways. We talked for maybe 15 minutes about the Cholas and Pandyas and the dreaded Chalukas and had a grand time of it. Finally Mo asked if we could take his picture, and he said certainly, as I long as he got one of him and me together. We took said picture, and I got his email address so that I could email it to him.

I don't know if I even meant to follow through on it, it was just a sudden thing that I did because I realized I had a pencil in my pocket and a blank page at the back of my Lonely Planet guide. He, equally, looked like he didn't expect me to actually email him anything. We both knew it was a pleasant meeting at a world monument, and were both content to let it go at that. I know that in North America I certainly would have been more than happy it was over there. I have a tendency towards misanthropism and anti-social behavior that lead one of my high school guidance counselors to jokingly suggest that I be voted most likely to hide in a cabin and write a manifesto.

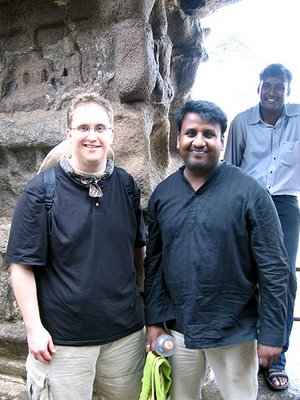

When we got back home to Chennai and we downloaded the 1746 pictures we had taken over the past 36 hours I found the picture of Murali and I coming up on top of the stack, sorted by my computer for its own mysterious reasons. I looked at the picture and thought how much of a type we seemed – a little big around the middle, kinda dorky and friendly and harmless looking, both obviously in a place we'd read and dreamed about since we were kids, and both obviously getting our picture taken with a stranger in a way that was not our normal mode of operation. So I succumbed to the hospitality of India and emailed him a copy of the picture. Along with it I dashed a quick note, saying I'd be in town for at least a month more and if he wanted to have coffee and talk about world politics or history I'd love to meet him again. I sent it off, figured he'd never respond, and went about my week.

By the time the response came I'd almost forgotten about the note. Murali thought it was a great idea that we get together, but thought he could do better than coffee – he suggested that Mo and I come over to his house for a traditional South Indian dinner with he and his wife. I'd met this guy by accident, talked to him for 15 minutes, and now he was inviting me to his house for dinner. This sort of thing doesn't happen in North America, or at least doesn't happen to me. And if it did I'd find a way to beg off quick, fast, and in a hurry. So of course I said yes. I was, after all, in India. We worked out the details: veg meal, he'd pick us up at the hotel and drop us off afterwards, 5:00 meeting time, we needn't bring anything.

The next several days had frequent moments of worry and excitement, even more so for Mo than for me. We were going to a real Indian house to eat real Indian food with a couple who were our age, our social position, our education level, and very much like us in every way -- but who were also from a different world altogether. We worried that the food might make us sick, might be to spicy, we debated what to do if they offered us water (Chennai water is notoriously bad, even for India), and if we should bring a present or what. We weren't sure how to dress, formal or un, and if formal how fancy? We didn't want to show up dressed like we were going to a formal dinner if they were going to be in jeans and t-shirts, and vice versa, and we had no idea what to expect. Most of all we wondered if they were as nervous as we were.

When the night in question came around Mo was so wound she was just about jumping out of her skin. I was calmer about it by that point, as I'd done my normal trick and worked all my nervous energy out before the moment and was fairly placid now that it was actually there. We wait for Murali, and I run back to the room to get my glasses. Of course he shows up while I'm gone, and he and Mo have to find each other and talk until I get there. Now in the west this would be less of a big deal, but in India relations between the sexes are very formalized, and a man talking to another man's wife without him present is rather socially difficult. So they were both very relived when I showed up, glasses in hand, and we all headed to the car.

It was at that point that the apologies started. I've heard that there is an Indian expression, "If you wish a happy evening do not invite the elephant into the house." It gets used in relation to westerners a lot, to mean that we're so used to fine things, to a certain standard of living and prosperity that for an Indian to invite one of us into his house is to invite our scorn and contempt. It is I've since come to understand an expression used with more than a little justification. I've seen some ugly Americanisms since I've been here, and even the most well meaning folks can give away more with their faces then they might dream they're communicating.

Murali apologized to us that his car was so small, and was sure that it would not be comfortable for large-bodied Mo and I. This in a city where we'd gotten around mostly by foot or by tuck-tuck and were now being offered a ride in an air conditioned car with nice seats and stereo. We assured him that the car was fine, and as we headed towards his house he apologized that his house was so small and simple. Murali, you see, had lived in Chicago and been taken out to dinner by the bosses at some major auto companies, and so his impression of North Americans was Lexi and the types of houses you saw in Feris Buller's Day Out. He knew for a fact that even though he was doing well for India his standard was not our standard, and his hands were white-knuckled and sweating on the steering wheel as we got out of the fancy part of town and into the sticks where his house was. In trying to reassure him I told him we don't even own a car, and we have only a very small condo of our own – probably even smaller than his place. This reassured him very slightly, until I made the mistake of saying that we lived on the 23rd floor of our building. I don't know if there is a 23 story building in Chennai, and the only condos that high in the loop in Chicago cost a chunk of bills. By accident I had just reminded him he had an elephant in the car.

It wasn't long after that when Murali said to us, "Well, this will be an experience for you. I don't know if it will be good, but it will be a different world." I laughed at this point and told him it was all good so far. By that point we'd passed the burning grounds at the edge of the city proper and were headed out into a neighborhood where the narrow and twisting roads were only occasionally paved, where water buffalo and brahma bulls crowded the bicycles off to the shoulder and we were the only automobile in sight. We went past the crowd of buildings built one on top of each other at the edge of the "major street" and into a green land of little paddies, fields with tall stalks growing, and deep ditches lined with verdant grass and palm trees. At the edge of one such street was Murali's house: small and white, surrounded by a walled courtyard and a little garden.

By this point it had started raining, a thick pounding Indian monsoon rain that soaked anything that stepped out into it. Murali honked to get his wife to come out and open the gate, but she wouldn't come out. He leaped out and opened the gate, refusing to let us help because we couldn't get wet. He then drove us under the patio and made sure there was a dry place for us to get out, showing the kind of gallant hospitality that you don't see in our world anymore. I swear that if he'd had a coat he would have laid it down at Mo's feet so she could walk on it rather than in the water.

On entering the house we found out why his wife hadn't come into the rain to let us in – she was dressed in a beautiful sari, jasmine in her hair and bells on her ankles. She'd obviously spent a lot of time making sure she looked proper and elegant, and there was no way she was ruining that by getting wet. It was just as obvious that she was so nervous that she was about to vibrate her way through one of the walls. If it was tough for Murali to have us in his house it must have been a thousand times harder for Suganya, the woman of the house and the one upon whom its cleanliness, livability, and class reflected most. We found out later that she also used to work at the company where Mo is training. She was a common floor rep and knew damn well that Mo was a big time international consultant – the kind who not too long before could have had her and everyone she knew fired with a single stroke of a pen. And now we were in her house.

She needn't have worried. While the house was simple by western standards it was beautiful and spotlessly clean. And I do mean spotlessly. There was not a speck of dust anywhere in that entire house. Not a cobweb under the couch, not a smuch of dirt along one floorboard, nor any sign of the overwhelming odor of human habitation that fills all of India like a smog. I've never seen a house so well tended anywhere, and to see it in the very often busily messy middle of India was a revelation.

We gave her sweets from Sri Krsna, a popular local store that hand makes fresh Indian sweets daily, and this caused her to laugh and laugh as Murali offered us a seat. We found out later that when you first visit the home of an old friend, especially an old friend you have not seen since her marriage, it is traditional to bring sweets. This completely accidental gesture of ours helped ease her somewhat, and not long after she invited us into the kitchen to see her hearth and the center of her house. This, incidentally, is a huge honor. In Mo's cultural training she was told that you do not go into an Indian kitchen ever unless you are specifically invited, for it is the symbol of the house's well being and the center of the woman of the house's power. Indeed, Murali himself did not set foot in the kitchen, leaving our side by the door and saying, "That place is hers, she must show you."

The main room of the house had been much like the living room of a western house. The kitchen, otoh, was not. The dishes, the pans, the foods… all had different shapes, were arranged in different ways. There were a million flat pans and a thousand deep pots, not many having the familiar profiles of frying pans or sauce pots. The refrigerator was small, and with a lovely and delicate flower painted blossoming across its face. Murali later told us that Suganya had painted it, and all the glass work in the house. Everything in her home has her touch upon it, you see, and everything must be as beautiful as possible.

As we left the kitchen Murali showed us the house's shrine, were Ganesh and Shiva sat. We asked if he did puja (worship) daily, and he said not so much – he was very busy you see. Suganya, on the other hand, hastened to assure us that she prayed and did puja daily. I got the sense that she was much more traditional than Murali. This is a pattern I've seen often in Indian houses since: a wife who still follows the old ways of puja closely and a husband who still very much believes in the gods, but not in idols or daily pujas.

We then spent some time talking with Murali while Suganya finished cooking. We talked about the caste system, about education and the future of India's political system, about the difference between the country and the city in Indian life, and a million other things. Murali got visibly tense every time we talked about caste, and you could just tell he'd had bad experiences talking about it with Americans in the past. That we didn't immediately level judgment against the very concept surprised him somewhat, and gave him a chance to express his opinions about it – which can be summed up that once everyone is educated caste will vanish. It will take time, he said, but it is already walking dead and just doesn't know it yet.

We queried about his caste and found that he was a kshatriya of a mid-level chivalrous jati, as was Suganya. Theirs was an arranged marriage, and they had been married for just under a year. She quit her job not long after they were married, and now kept the house. Later we found out that she had spent 5 hours making us dinner, and that in the life of the average South Indian woman this is not much time to spend daily in the kitchen. Things like premixed spice mixes and batter mixes have cut the time down from what it was in the time of their mothers, who spent most of their day cooking for their large families in little villages north and west of Madurai.

While we were talking Suganya served us juice, water, and potato patties as an appetizer. Mo and I had decided before coming that we were going to trust whatever they gave us, despite all the dire warnings we'd been given about how white people sometimes died from drinking Chennai water. As it turns out we were right to. Suganya had cooked everything in bottled water and serves us nothing that was not 100% safe. I doubt we could have had a safer meal anywhere in all of India.

After the appetizers Murali's brother joined us. He's living in their house while he works on his MBA at one of the Oxford associated colleges in Chennai. Friendly and charismatic he none the less seemed a bit bemused that we were over for dinner, like he couldn't believe that his brother had really turned his introduction into a dinner with the Americans. He was also much concerned by the fact that in the picture of Murali and I he was out of focus, and asked if we could get a new picture before we left in which he was in focus.

Moments after his entrance the thunder started to fall outside, and the rain pounded down around us, echoing in the little pond just outside the window while the wind came howling up. The electricity didn't last long under this assault, and the whole house went dark and all the fans went out. Murali went searching for candles muttering "oh shit oh shit" under his breath in a manner most Indian despite the utter non-Indianness of the words he was using. The apologies started up again, but these we were able to put aside by talking about the blackout in Toronto where we lost power for 3 days.

Dinner was thus served by candle light, during monsoon rains and howling winds in a little Indian house beside a pond. I can't possible imagine a more perfect moment, it was like all of the books I'd ever read about India suddenly loomed up around me, letting me feel that this was a perfect moment that was part of a world that was fading fast. If it hadn't been for the storm we would have eaten under electric lights and the fans would have drowned out the sound of the rain. But as it was there was the night and the humidity, the sound of frogs and falling drops, the smell of jasmine and the dreams of this wet and reincarnating land.

The food was exquisite, of course. There were six courses, all made by hand. There were idli and sambar and rice noodles served with sweetened coconut milk, halva and sambar, tangy rice and sweet rice, potato patties rich with onion and curry, dumplings of lentil, and ice cream for desert. We ate with our hands, which is harder to do than you'd think, but our hosts showed us how to do so with proper Tamil table manners and in the end we successfully stuffed our bellies without making too much fools of ourselves.

One thing, however, did make dinner distinctly odd. As we sat down to eat Murali and Suganya did not. Murali says to me, "I know this is not your way, but it is ours. So we will serve you while you eat." So for the rest of dinner our host and hostess stand by the table, serving us onto our plates, while we and Murali's brother eat our fill. Murali claimed that they ate in the kitchen between courses, but I don’t know if that is true. I think they waited until after we were gone to eat. (And even then poor Murali got no sweets or ice cream, as Suganya doesn't allow it since his cholesterol results came back high last time at the doctor.)

Much as I loved the dinner I can't express how odd this made me feel. Both Mo and I come from rather blue-collar backgrounds (farmers and miners) and the concept of being served is hard on us at the best of times. Having your host and hostess, who are rapidly becoming your friends, stand by and serve you without eating themselves is downright unnerving. Caught between the vice of personal discomfort and cultural respect we said nothing, and let them serve us in their own home. Others of my Indian friends have told us this is a great honor, both to us and to them, for it shows respect and hospitality and our trust in them. But I tell you, at the time it was nothing short of disconcerting.

After dinner Suganya came out to join us in talking for another hour or so. She talked to us about making food in Canada, and asked us how much time we have to spend cooking every day. The concept of mixes and quick-fix meals was fascinating to her, as the amount of free time one can gain by needing to spend as little as two hours a day cooking (yes, you read that right) is something she is very excited about. We also got to hear about how she felt she should have been born in America as she doesn't like Indian food nearly as much as she loves hamburgers and pizza. Murali informed us that she eats Pizza Hut every chance she gets.

As we finally went to take our leave Murali ran into the back room and brought out a present, a perfect statue of Ganesh, hand carved from some lightly colored but dense wood. It was only after we got home that we realized it was signed by the artist and is probably part of a limited series. After dinner, hospitality, and a free ride they got us a present as well. That is Indian hospitality, the degree of love and generosity and warmth that fills this country and its people in their best moments.

Murali then drove us home and explained how cricket works. By the end of the long drive back to the hotel he'd gotten comfortable enough with us to talk about world politics – particularly America and Pakistan's relationship and how it always confuses him that America sides with Pakistan above India, despite the fact that India is a secular democracy. It was good to see him relaxing enough to get into touchy matters like that, after the nervousness of the drive to his house. When we told him we'd have to have him over for dinner at the hotel he agree with cheer and hardly a nerve at all.

As a note on the picture, we all look demented because the picture was taken durring the blackout. It was taken it pitch darkness, with Mo guessing where the focus was. That it turned out at all is a minor miracle. That I look a dork is normal. I can't take a picture in India without looking like a hopeless nerd.

We’ve since had them over for dinner at the hotel restaurant. As luck had it we were able to take them to a nice Italian buffet, and to buy Suganya a lovely pizza and sneak Murali some cheesecake while she wasn't working. We gave them a present of pure Canadian maple syrup, flags, and a Toronto bag. This time waiters served us, and we were able to all eat together and talk about India and Canada and politics and everything under the sun.

Murali and Suganya say that they now must visit Toronto, and when they do they have been invited to our house for dinner. I will make them pizza and devil's food cake from scratch (my specialties) and we will tour them around the city. Our only request has been that they not come in the winter, as we're not sure that Suganya (who isn't used to temperatures below 20 degrees Celsius) would survive it.

This is why I love India. It has been a very long time since I was able to make a friend from a random meeting in North America. Part of it is our culture, and a much larger part of it is me. But here we were able to turn a chance meeting into a friendship. As Murali said as we were taking pictures as they prepared to leave after our last dinner, "I think we are connected now. Even if we are far apart we are always friends."

While Mo and I were in the Shore Temple, looking into the shrine of Shiva in the far back of that monolithic structure, this fellow offered me his hand and asked me if I knew the history of the place where I was standing. Behind him his wife was laughing at him, saying "Oh Murali!" and his brother was shaking his head with the kind of dismay that said very clearly that Murali was at it again – talking to the Americans.

I shook his hand and grinned and said, "I know a little, it was…" and proceeded to tell him the story that I told in my entry Mamallapuram I. This both delighted, startled, and slightly concerned him. He was, all at once, happy that I knew about his country, surprised that I knew so much, and a little concerned that I might know more than him. But as I settled in to pump him for further information he relaxed, though his wife and brother continued to laugh at him and his odd ways. We talked for maybe 15 minutes about the Cholas and Pandyas and the dreaded Chalukas and had a grand time of it. Finally Mo asked if we could take his picture, and he said certainly, as I long as he got one of him and me together. We took said picture, and I got his email address so that I could email it to him.

I don't know if I even meant to follow through on it, it was just a sudden thing that I did because I realized I had a pencil in my pocket and a blank page at the back of my Lonely Planet guide. He, equally, looked like he didn't expect me to actually email him anything. We both knew it was a pleasant meeting at a world monument, and were both content to let it go at that. I know that in North America I certainly would have been more than happy it was over there. I have a tendency towards misanthropism and anti-social behavior that lead one of my high school guidance counselors to jokingly suggest that I be voted most likely to hide in a cabin and write a manifesto.

When we got back home to Chennai and we downloaded the 1746 pictures we had taken over the past 36 hours I found the picture of Murali and I coming up on top of the stack, sorted by my computer for its own mysterious reasons. I looked at the picture and thought how much of a type we seemed – a little big around the middle, kinda dorky and friendly and harmless looking, both obviously in a place we'd read and dreamed about since we were kids, and both obviously getting our picture taken with a stranger in a way that was not our normal mode of operation. So I succumbed to the hospitality of India and emailed him a copy of the picture. Along with it I dashed a quick note, saying I'd be in town for at least a month more and if he wanted to have coffee and talk about world politics or history I'd love to meet him again. I sent it off, figured he'd never respond, and went about my week.

By the time the response came I'd almost forgotten about the note. Murali thought it was a great idea that we get together, but thought he could do better than coffee – he suggested that Mo and I come over to his house for a traditional South Indian dinner with he and his wife. I'd met this guy by accident, talked to him for 15 minutes, and now he was inviting me to his house for dinner. This sort of thing doesn't happen in North America, or at least doesn't happen to me. And if it did I'd find a way to beg off quick, fast, and in a hurry. So of course I said yes. I was, after all, in India. We worked out the details: veg meal, he'd pick us up at the hotel and drop us off afterwards, 5:00 meeting time, we needn't bring anything.

The next several days had frequent moments of worry and excitement, even more so for Mo than for me. We were going to a real Indian house to eat real Indian food with a couple who were our age, our social position, our education level, and very much like us in every way -- but who were also from a different world altogether. We worried that the food might make us sick, might be to spicy, we debated what to do if they offered us water (Chennai water is notoriously bad, even for India), and if we should bring a present or what. We weren't sure how to dress, formal or un, and if formal how fancy? We didn't want to show up dressed like we were going to a formal dinner if they were going to be in jeans and t-shirts, and vice versa, and we had no idea what to expect. Most of all we wondered if they were as nervous as we were.

When the night in question came around Mo was so wound she was just about jumping out of her skin. I was calmer about it by that point, as I'd done my normal trick and worked all my nervous energy out before the moment and was fairly placid now that it was actually there. We wait for Murali, and I run back to the room to get my glasses. Of course he shows up while I'm gone, and he and Mo have to find each other and talk until I get there. Now in the west this would be less of a big deal, but in India relations between the sexes are very formalized, and a man talking to another man's wife without him present is rather socially difficult. So they were both very relived when I showed up, glasses in hand, and we all headed to the car.

It was at that point that the apologies started. I've heard that there is an Indian expression, "If you wish a happy evening do not invite the elephant into the house." It gets used in relation to westerners a lot, to mean that we're so used to fine things, to a certain standard of living and prosperity that for an Indian to invite one of us into his house is to invite our scorn and contempt. It is I've since come to understand an expression used with more than a little justification. I've seen some ugly Americanisms since I've been here, and even the most well meaning folks can give away more with their faces then they might dream they're communicating.

Murali apologized to us that his car was so small, and was sure that it would not be comfortable for large-bodied Mo and I. This in a city where we'd gotten around mostly by foot or by tuck-tuck and were now being offered a ride in an air conditioned car with nice seats and stereo. We assured him that the car was fine, and as we headed towards his house he apologized that his house was so small and simple. Murali, you see, had lived in Chicago and been taken out to dinner by the bosses at some major auto companies, and so his impression of North Americans was Lexi and the types of houses you saw in Feris Buller's Day Out. He knew for a fact that even though he was doing well for India his standard was not our standard, and his hands were white-knuckled and sweating on the steering wheel as we got out of the fancy part of town and into the sticks where his house was. In trying to reassure him I told him we don't even own a car, and we have only a very small condo of our own – probably even smaller than his place. This reassured him very slightly, until I made the mistake of saying that we lived on the 23rd floor of our building. I don't know if there is a 23 story building in Chennai, and the only condos that high in the loop in Chicago cost a chunk of bills. By accident I had just reminded him he had an elephant in the car.

It wasn't long after that when Murali said to us, "Well, this will be an experience for you. I don't know if it will be good, but it will be a different world." I laughed at this point and told him it was all good so far. By that point we'd passed the burning grounds at the edge of the city proper and were headed out into a neighborhood where the narrow and twisting roads were only occasionally paved, where water buffalo and brahma bulls crowded the bicycles off to the shoulder and we were the only automobile in sight. We went past the crowd of buildings built one on top of each other at the edge of the "major street" and into a green land of little paddies, fields with tall stalks growing, and deep ditches lined with verdant grass and palm trees. At the edge of one such street was Murali's house: small and white, surrounded by a walled courtyard and a little garden.

By this point it had started raining, a thick pounding Indian monsoon rain that soaked anything that stepped out into it. Murali honked to get his wife to come out and open the gate, but she wouldn't come out. He leaped out and opened the gate, refusing to let us help because we couldn't get wet. He then drove us under the patio and made sure there was a dry place for us to get out, showing the kind of gallant hospitality that you don't see in our world anymore. I swear that if he'd had a coat he would have laid it down at Mo's feet so she could walk on it rather than in the water.

On entering the house we found out why his wife hadn't come into the rain to let us in – she was dressed in a beautiful sari, jasmine in her hair and bells on her ankles. She'd obviously spent a lot of time making sure she looked proper and elegant, and there was no way she was ruining that by getting wet. It was just as obvious that she was so nervous that she was about to vibrate her way through one of the walls. If it was tough for Murali to have us in his house it must have been a thousand times harder for Suganya, the woman of the house and the one upon whom its cleanliness, livability, and class reflected most. We found out later that she also used to work at the company where Mo is training. She was a common floor rep and knew damn well that Mo was a big time international consultant – the kind who not too long before could have had her and everyone she knew fired with a single stroke of a pen. And now we were in her house.

She needn't have worried. While the house was simple by western standards it was beautiful and spotlessly clean. And I do mean spotlessly. There was not a speck of dust anywhere in that entire house. Not a cobweb under the couch, not a smuch of dirt along one floorboard, nor any sign of the overwhelming odor of human habitation that fills all of India like a smog. I've never seen a house so well tended anywhere, and to see it in the very often busily messy middle of India was a revelation.

We gave her sweets from Sri Krsna, a popular local store that hand makes fresh Indian sweets daily, and this caused her to laugh and laugh as Murali offered us a seat. We found out later that when you first visit the home of an old friend, especially an old friend you have not seen since her marriage, it is traditional to bring sweets. This completely accidental gesture of ours helped ease her somewhat, and not long after she invited us into the kitchen to see her hearth and the center of her house. This, incidentally, is a huge honor. In Mo's cultural training she was told that you do not go into an Indian kitchen ever unless you are specifically invited, for it is the symbol of the house's well being and the center of the woman of the house's power. Indeed, Murali himself did not set foot in the kitchen, leaving our side by the door and saying, "That place is hers, she must show you."

The main room of the house had been much like the living room of a western house. The kitchen, otoh, was not. The dishes, the pans, the foods… all had different shapes, were arranged in different ways. There were a million flat pans and a thousand deep pots, not many having the familiar profiles of frying pans or sauce pots. The refrigerator was small, and with a lovely and delicate flower painted blossoming across its face. Murali later told us that Suganya had painted it, and all the glass work in the house. Everything in her home has her touch upon it, you see, and everything must be as beautiful as possible.

As we left the kitchen Murali showed us the house's shrine, were Ganesh and Shiva sat. We asked if he did puja (worship) daily, and he said not so much – he was very busy you see. Suganya, on the other hand, hastened to assure us that she prayed and did puja daily. I got the sense that she was much more traditional than Murali. This is a pattern I've seen often in Indian houses since: a wife who still follows the old ways of puja closely and a husband who still very much believes in the gods, but not in idols or daily pujas.

We then spent some time talking with Murali while Suganya finished cooking. We talked about the caste system, about education and the future of India's political system, about the difference between the country and the city in Indian life, and a million other things. Murali got visibly tense every time we talked about caste, and you could just tell he'd had bad experiences talking about it with Americans in the past. That we didn't immediately level judgment against the very concept surprised him somewhat, and gave him a chance to express his opinions about it – which can be summed up that once everyone is educated caste will vanish. It will take time, he said, but it is already walking dead and just doesn't know it yet.

We queried about his caste and found that he was a kshatriya of a mid-level chivalrous jati, as was Suganya. Theirs was an arranged marriage, and they had been married for just under a year. She quit her job not long after they were married, and now kept the house. Later we found out that she had spent 5 hours making us dinner, and that in the life of the average South Indian woman this is not much time to spend daily in the kitchen. Things like premixed spice mixes and batter mixes have cut the time down from what it was in the time of their mothers, who spent most of their day cooking for their large families in little villages north and west of Madurai.

While we were talking Suganya served us juice, water, and potato patties as an appetizer. Mo and I had decided before coming that we were going to trust whatever they gave us, despite all the dire warnings we'd been given about how white people sometimes died from drinking Chennai water. As it turns out we were right to. Suganya had cooked everything in bottled water and serves us nothing that was not 100% safe. I doubt we could have had a safer meal anywhere in all of India.

After the appetizers Murali's brother joined us. He's living in their house while he works on his MBA at one of the Oxford associated colleges in Chennai. Friendly and charismatic he none the less seemed a bit bemused that we were over for dinner, like he couldn't believe that his brother had really turned his introduction into a dinner with the Americans. He was also much concerned by the fact that in the picture of Murali and I he was out of focus, and asked if we could get a new picture before we left in which he was in focus.

Moments after his entrance the thunder started to fall outside, and the rain pounded down around us, echoing in the little pond just outside the window while the wind came howling up. The electricity didn't last long under this assault, and the whole house went dark and all the fans went out. Murali went searching for candles muttering "oh shit oh shit" under his breath in a manner most Indian despite the utter non-Indianness of the words he was using. The apologies started up again, but these we were able to put aside by talking about the blackout in Toronto where we lost power for 3 days.

Dinner was thus served by candle light, during monsoon rains and howling winds in a little Indian house beside a pond. I can't possible imagine a more perfect moment, it was like all of the books I'd ever read about India suddenly loomed up around me, letting me feel that this was a perfect moment that was part of a world that was fading fast. If it hadn't been for the storm we would have eaten under electric lights and the fans would have drowned out the sound of the rain. But as it was there was the night and the humidity, the sound of frogs and falling drops, the smell of jasmine and the dreams of this wet and reincarnating land.

The food was exquisite, of course. There were six courses, all made by hand. There were idli and sambar and rice noodles served with sweetened coconut milk, halva and sambar, tangy rice and sweet rice, potato patties rich with onion and curry, dumplings of lentil, and ice cream for desert. We ate with our hands, which is harder to do than you'd think, but our hosts showed us how to do so with proper Tamil table manners and in the end we successfully stuffed our bellies without making too much fools of ourselves.

One thing, however, did make dinner distinctly odd. As we sat down to eat Murali and Suganya did not. Murali says to me, "I know this is not your way, but it is ours. So we will serve you while you eat." So for the rest of dinner our host and hostess stand by the table, serving us onto our plates, while we and Murali's brother eat our fill. Murali claimed that they ate in the kitchen between courses, but I don’t know if that is true. I think they waited until after we were gone to eat. (And even then poor Murali got no sweets or ice cream, as Suganya doesn't allow it since his cholesterol results came back high last time at the doctor.)

Much as I loved the dinner I can't express how odd this made me feel. Both Mo and I come from rather blue-collar backgrounds (farmers and miners) and the concept of being served is hard on us at the best of times. Having your host and hostess, who are rapidly becoming your friends, stand by and serve you without eating themselves is downright unnerving. Caught between the vice of personal discomfort and cultural respect we said nothing, and let them serve us in their own home. Others of my Indian friends have told us this is a great honor, both to us and to them, for it shows respect and hospitality and our trust in them. But I tell you, at the time it was nothing short of disconcerting.

After dinner Suganya came out to join us in talking for another hour or so. She talked to us about making food in Canada, and asked us how much time we have to spend cooking every day. The concept of mixes and quick-fix meals was fascinating to her, as the amount of free time one can gain by needing to spend as little as two hours a day cooking (yes, you read that right) is something she is very excited about. We also got to hear about how she felt she should have been born in America as she doesn't like Indian food nearly as much as she loves hamburgers and pizza. Murali informed us that she eats Pizza Hut every chance she gets.

As we finally went to take our leave Murali ran into the back room and brought out a present, a perfect statue of Ganesh, hand carved from some lightly colored but dense wood. It was only after we got home that we realized it was signed by the artist and is probably part of a limited series. After dinner, hospitality, and a free ride they got us a present as well. That is Indian hospitality, the degree of love and generosity and warmth that fills this country and its people in their best moments.

Murali then drove us home and explained how cricket works. By the end of the long drive back to the hotel he'd gotten comfortable enough with us to talk about world politics – particularly America and Pakistan's relationship and how it always confuses him that America sides with Pakistan above India, despite the fact that India is a secular democracy. It was good to see him relaxing enough to get into touchy matters like that, after the nervousness of the drive to his house. When we told him we'd have to have him over for dinner at the hotel he agree with cheer and hardly a nerve at all.

As a note on the picture, we all look demented because the picture was taken durring the blackout. It was taken it pitch darkness, with Mo guessing where the focus was. That it turned out at all is a minor miracle. That I look a dork is normal. I can't take a picture in India without looking like a hopeless nerd.

We’ve since had them over for dinner at the hotel restaurant. As luck had it we were able to take them to a nice Italian buffet, and to buy Suganya a lovely pizza and sneak Murali some cheesecake while she wasn't working. We gave them a present of pure Canadian maple syrup, flags, and a Toronto bag. This time waiters served us, and we were able to all eat together and talk about India and Canada and politics and everything under the sun.

Murali and Suganya say that they now must visit Toronto, and when they do they have been invited to our house for dinner. I will make them pizza and devil's food cake from scratch (my specialties) and we will tour them around the city. Our only request has been that they not come in the winter, as we're not sure that Suganya (who isn't used to temperatures below 20 degrees Celsius) would survive it.

This is why I love India. It has been a very long time since I was able to make a friend from a random meeting in North America. Part of it is our culture, and a much larger part of it is me. But here we were able to turn a chance meeting into a friendship. As Murali said as we were taking pictures as they prepared to leave after our last dinner, "I think we are connected now. Even if we are far apart we are always friends."

2 Comments:

I only remember that this journal exists every once in awhile, but I'm always glad when I do.

Man, I teared up reading this. Sometimes it takes someone who's there and who understands to remind you what you miss. While the specific customs are somewhat different, Indonesia is very much like this.

The openness is something that I miss, but have half-forgotten being back in the states, and being reminded of it helps renew my resolve to be different. Approach more people, make more friend, bring some of that generosity and hospitality to the US where it is so sorely needed.

Thanks.

Thomas

Post a Comment

<< Home